AADL Talks To: Ken Burns, Documentary Filmmaker

In this episode, AADL Talks To Ken Burns. Ken is a documentary filmmaker known for his critically acclaimed films exploring all facets of American culture. Ken reflects on growing up and coming of age in Ann Arbor during the 1960s, and how this period of intense political and cultural activity mixed with family tragedy charted his journey. He takes us down the streets we remember -- past restaurants and theaters that have come and gone -- and through a back alleyway during the 1969 South University Street Riot. Along the way, he highlights the people, places, and vibrant musical and cinema culture that left its mark on his work.

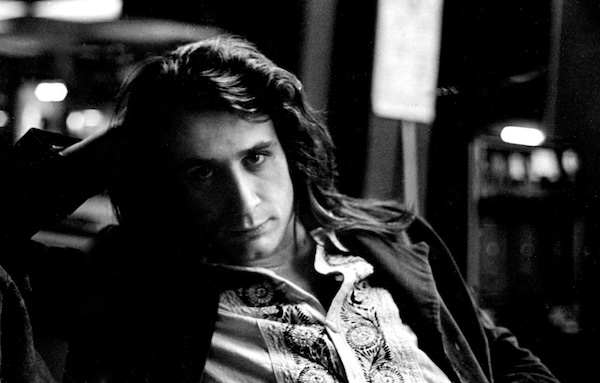

AADL Talks To: Bill Ayers

Bill Ayers is a retired Distinguished Professor of Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago. During his time in Ann Arbor during the 1960s, he served as director of Ann Arbor's experimental Children's Community School; Education Secretary for the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS); and co-founder of the militant Weather Underground organization, which originated in Ann Arbor in 1969 as a far left-wing revolutionary party.

Ayers traces the path of his political awakening from wide-eyed college freshman to seasoned student organizer and educator. He reflects on the tumultuous moral dilemma he and many activists faced as the Vietnam War raged on in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He discusses the factionalism within the SDS leadership that resulted in the formation of the Weather Underground; how the strands of student activism during this turbulent time were rooted in the moral agenda outlined by Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.; and his lifelong pedagogic commitment to education.

AADL Talks To: Peter Andrews

In this wide-ranging interview from 2010, Peter Andrews recalls his varied career producing and managing local and regional music talent — from managing the Scot Richard Case (SRC) band and bringing bands like The Who, Jimi Hendrix, and the Yardbirds to Ann Arbor’s Fifth Dimension club, to booking national acts for University of Michigan student groups. He also discusses his role in Ann Arbor’s legendary Blues and Jazz Festivals, producing the John Sinclair Freedom Rally at Crisler Arena in 1971, and bringing John Lennon and Yoko Ono to town.

Gary Grimshaw: An Interview

John Sinclair in Front of Former White Panther House on Hill Street, March 1991 Photographer: Peter Yates

Year:

1991

In Ann Arbor, the 'Summer of Love' was a time of political protests

The 1969 South University Riot

The 1969 South University Riot was a series of confrontations between local law enforcement and factions of Ann Arbor’s counterculture population that extended over three nights, from June 16-18, on or near the four-block South University Avenue shopping district in Ann Arbor.

Monday, June 16

Varying accounts in local and regional media make it difficult to determine exactly what occurred on the first night, June 16, but according to the Ann Arbor News, events began around 10:00 pm when an Ann Arbor police officer attracted a crowd of about 50 people while attempting to ticket a motorcyclist for stunt-riding in the street. The officer called for reinforcements and four additional police cars arrived, but when they eventually left without issuing the motorcyclist a ticket, the crowd -- now estimated at about 300 and comprised of various countercultural groups -- celebrated by staging a spontaneous "liberation party" and cordoning off a block of South University Avenue with tires, boards, garbage cans, and similar items.

Over the next few hours, the crowd swelled to somewhere between 500 and 1000, and members engaged in activities such as dancing, singing, drinking, and throwing firecrackers. Local newspapers also reported that a couple engaged in sexual relations in the middle of South University Avenue. During the revelry, Ann Arbor Police Chief Walter E. Krasny requested that both the Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Department and Michigan State Police be on standby in the nearby town of Ypsilanti. Plain clothes police officers were sent in to observe the crowd, but no tickets were issued out of fear that it would cause an “instant riot,” as Lieutenant Eugene Staudenmaeir told the campus newspaper The Michigan Daily. (Ann Arbor Police Chief Walter Krasny would later state that they declined to issue tickets because of “limited manpower.”) The crowd eventually broke up around 1:00 am, with some attendees returning to sweep up the debris and broken glass. Damages were minor, with some broken windows and slogans painted on parking signs and shop windows.

Tuesday, June 17

Although Monday’s event appeared to occur spontaneously, expectations were high for the next night, June 17, after some among Monday night’s attendees were overheard declaring they would attempt another street party on Tuesday at the same time and location. Furthermore, members of the White Panther Party, a local radical anti-establishment organization, issued a statement calling for the transformation of the South University Avenue shopping area into a pedestrian mall or “people’s park,” a pointed reference to the recent People’s Park movement in Berkeley, California that had been violently suppressed only a month prior. As a result, reporters from Detroit and further afield were in attendance that evening; and several high-ranking local officials, among them Washtenaw County Sheriff Douglas Harvey, Ann Arbor Police Chief Walter E. Krasny, and Prosecuting attorney William F. Delhey, made plans for a “show of force if the ‘street liberations’” took place.

Crowds began to gather in the early evening and by 8:00 pm attendees were participating in a variety of activities: Some erected a barricade of traffic cans, signs, and similar materials; two girls sat down in the middle of the street blocking a car; others set a fire in a garbage can. At around 9:00 pm the crowd had reached roughly 1,000 people, some of whom were merely onlookers hoping for a show. Deputy Police Chief Harold E. Olson attempted to disperse the crowd with the use of a bullhorn, but when he was met with resistance and shouted obscenities, riot-equipped officers from city and county agencies, including nearby Oakland and Monroe counties, were instructed to advance on the crowd, moving westward, with nightsticks, rifles held at port arms, and a half dozen crowd-control dogs from the Sheriff’s Department. Most of the crowd broke and ran, but a few people stood ground until they were seized and removed to an awaiting prisoner bus.

Further down the line, members of the crowd responded by hurling bricks, rocks, and bottles; some objects were thrown from the tops of buildings on either side of South University Avenue. Sheriff Harvey countered these efforts by ordering the firing of tear gas in their direction. Police cleared the street in roughly one hour, making 25 arrests, while some officers traveled further afield onto private property and the U-M campus, using tear gas and flares to illuminate gatherings that had reformed there.

Following the dispersal of the crowd, the area remained relatively quiet, with the exception of periodic police routings of stragglers, until around midnight when another crowd of about 800 gathered near U-M President Robben Fleming’s house a little further west on South University Avenue. Fleming appeared briefly, trying but failing to calm down the crowd. Ken Kelly, a staff member of the Ann Arbor Argus, an underground newspaper, also tried in vain to persuade the crowd to move away.

During this period, President Fleming also engaged in a heated conversation with Sheriff Harvey, urging him to exercise restraint. Deputy Chief Olson, the other key command officer on the scene, agreed to grant the president some time, but when one of his riot officers was hit by a brick thrown from the crowd, he and Sheriff Harvey ordered their officers to advance. With the crowd still throwing rocks and officers swinging clubs, the confrontation split into three segments, one moving west on South University Avenue, others moving north or south on East University Avenue, and officers pursuing factions down side streets.

By 2:00 am it was over, with 47 arrests. Roughly half of those arrested were charged with “contention in the street,” a misdemeanor; the other half were charged with inciting a riot, a violation of Michigan’s new riot statute that was put in place following the Detroit Riots in 1967 and which was punishable by up to ten years in prison and/or a fine of up to $10,000. Several persons arrested were treated at hospitals for injuries sustained by police, and fifteen police officers were injured by flying rocks, bottles, and, in one instance, a flurry of cherry bombs.

President Fleming and Ann Arbor Mayor Robert Harris quickly issued statements generally supportive of police action; however, Fleming suggested that the use of tear gas caused more excitement than it helped. Other attendees, including Detroit News photographer James Hubbard, disagreed with this assessment of the previous night’s police action, stating that it was worse than what he’d experienced first-hand during the 1967 Detroit Riots.

Wednesday, June 18

During the day on June 18, an ad hoc alliance of local radicals and student government officials (the Radical Caucus, Students for a Democratic Society, and the Rent Strike Committee) staged a rally on central campus attended by nearly 1,000 people, including President Fleming, who urged students to remain calm. Lawrence (Pun) Plamondon, a leader in the White Panther Party, spoke on behalf of the group and asked the audience for a vote on whether they should demand that South University Avenue be closed immediately to make a pedestrian mall. The vote was turned down.

Meanwhile, hoping to avoid another night of conflict, university and city officials scheduled a free rock concert for 8:30 pm in Jefferson Plaza near the U-M Administration Building. During the concert, which was attended by roughly 2,000 people, Mayor Harris addressed the crowd, promising to appoint a special City Council committee to look into the viability of creating a pedestrian mall on South University Avenue or elsewhere in the vicinity. Several other university and city officials, including most members of Ann Arbor City Council, circulated among the crowd to talk with attendees and urge restraint.

There was no police presence at the concert. However, across town on South University Avenue, in anticipation of repeated conflict in that area, law enforcement presence included 300 police officers from six different agencies, an armored car with machine guns, and a police helicopter overhead.

No confrontations occurred during this period on South University Avenue, with most newspaper accounts describing a festive atmosphere and crowds diminishing by 11:00 pm. Shortly thereafter, however, a crowd once again began to form, blocking traffic in the street. When university officials and local clergy both failed to break it up, Deputy Chief Olson ordered roughly 200 police officers to either end of South University and, using a pincer movement with rifles leveled and bayonets fixed, closed in on the crowd.

20 arrests were made and two civilian injuries reported, including that of Dr. Edward Pierce, a physician, former Ann Arbor City councilman, mayoral candidate, and local Democratic Party chairman, who had attended at the request of U-M students for a trained medical presence. Dr. Pierce stated that police knocked him to the ground, struck him repeatedly with billy clubs, and dragged him 30 yards to the prisoner bus. Police claimed in return that Dr. Pierce had crossed the line of officers. He was arrested on a felony riot charge that was dropped the next morning.

Thursday, June 19, and the Aftermath

Although the atmosphere on South University Avenue remained somewhat tense on the following evening, Thursday, June 19, and police were held in a staging area nearby, city and university officials gambled that civilian peacekeeping efforts would be more effective than a show of police force - and their gamble paid off. Crowds thinned out by midnight and dispersed for good around 2:00 am when it started to rain heavily.

By most accounts, the confrontation between local law enforcement and factions of Ann Arbor’s counterculture - what the Detroit Free Press called “The Battle of Ann Arbor” - was a draw. Officials looking into the cause of the riot would later suggest that some attendees in the crowd that first night, June 16, may have been motivated to act out of frustration after attending a City Council meeting earlier that evening where they learned their favorite rock concerts at West Park would be canceled due to citizen complaints. However, the consensus seems to be that what started in the spirit of fun, or even frustration, never amounted to a serious or calculated take-over of South University property, despite attempts by more radical elements among the crowd to turn events in that direction.

The left and right were also divided on the use of police force. Letters to the city's newspaper, The Ann Arbor News, were strongly pro-police; whereas letters to the university’s student-run newspaper, The Michigan Daily, where almost universally anti-police and, in particular, anti-Sheriff Douglas Harvey. Ann Arbor Mayor Robert Harris was attacked from both sides - from the right for not hitting hard enough and from the left for not doing enough to hold back the police.

Learn More

White Panthers join the Peace Picnic at the Arboretum, July 1969 Photographer: Cecil Lockard

Year:

1969

Peace Picnic at the Arboretum, July 1969 Photographer: Cecil Lockard

Year:

1969

Ann Arbor News, July 7, 1969

Caption:

Sunday Afternoon At Arboretum About 300 persons spent a quiet afternoon at a "peace picnic" yesterday at the University's Arboretum, talking and singing. While officers patrol the area (top picture), groups of young people lounge on the grass. One group second picture) stages a brief White Panther rally while a father (third picture) warms his youngster with a jacket. Groups of singers and guitarist, (bottom picture) were scattered through the area. (News photos by Cecil Lockard)

- Read more about Peace Picnic at the Arboretum, July 1969

- Log in or register to post comments